This is a first-person story written by a mom who discovered her daughter has OSFED, the most common but little-recognized eating disorder with serious repercussions. Learn how she navigated finding out her daughter had OSFED and how they handle eating disorder recovery as a family.

By Serena Menken

As I waited to pick up my fifteen-year-old daughter Ellie from a partial hospitalization program at an eating disorders treatment center, a thought struck me:

“My daughter doesn’t look like the other teens here.”

The heavy, locked door swung open and a swarm of teens filed out to attach themselves to a parent. Most of the teens hid stick-thin legs in baggy sweats or pajama pants. I could see collarbones protruding and thin wrists peeking out of sleeves. The teens varied in height, in ethnicity, in gender. My daughter seemed like the only one who didn’t fit the mold for an underweight body. But she was just as sick as the rest of them.

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Free Guide: How Parents Can Help A Child With An Eating Disorder

Master the secrets to supporting a child with an eating disorder. Thousands of families like yours are stronger today because of these six vital lessons drawn from lived experience, best practices, and extensive study.

Stumbling on evidence

For years, I had worried about Ellie’s eating patterns. At times, she inhaled so much dessert at family dinner that she moaned in pain on the couch. Periodically, I would find bowls crusted with ice cream or the remains of frosting, hidden in her desk drawers or buried in her closet. When she was in fifth grade, we spent about six months living in other people’s homes while we hunted for a house with our realtor.

I remember stumbling upon a large stash of candy wrappers under Ellie’s bed, thinking, “We’ve only been here for a month. How did you manage to eat that much candy already and where did you get it?” As someone in long-term recovery from bulimia myself, I recognized the signs of compulsive overeating in my daughter. But I felt powerless to change her.

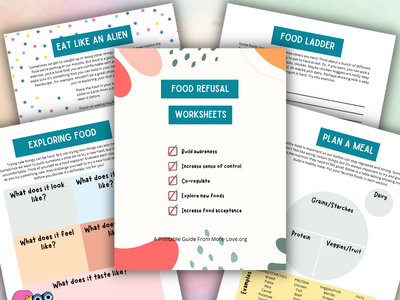

Since toddlerhood, Ellie refused to eat certain foods, such as fruits and vegetables. The daycare provider blamed me: You pureed her food for too long. Even in junior high, Ellie had sensory issues around food. She loved meat but only if ketchup (the right ketchup) was available. Her two safe vegetables were canned pureed pumpkin, which my husband bought by the case, and spinach leaves dipped in ketchup. Her only fruit was applesauce. She hated the texture of all other produce.

I tried to expand her palate

I tried so many techniques to expand her palate: coaching, encouragement, bribery, putting hated foods on her plate, requiring her to take just one bite. None of it worked. I just thought she was a picky eater. I didn’t know this was another form of an eating disorder called ARFID (Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder).

In seventh grade, Ellie stopped eating lunch at school. When I found uneaten sandwiches in her lunchbox, I asked her what happened. She brushed it away, saying that she wasn’t hungry or her stomach hurt. She said that she felt anxious at school and preferred to eat at home.

When I called the pediatrician, he asked if she might have anorexic tendencies. What? I asked, dazed. No, Ellie doesn’t restrict. I even asked her point-blank and she denied it with an easy smile. I believed her. My daughter wouldn’t lie to me, right? Even when we took her to therapy, no one said that she had anything more than generalized anxiety disorder.

Struggling and skipping meals

Fast forward to Ellie’s sophomore year in high school in Fall 2020. Ellie seemed more withdrawn and that she barely changed her clothes or bathed. I chalked it up to the stress of the pandemic, which shut down our entire city (including school) and forced us into isolation.

But when I looked more closely, I saw the truth: Ellie’s poor hygiene and isolation reflected the fact that she was struggling with depression. Ellie skipped family dinner more often than not, complaining of fatigue. Often, I woke up to find the kitchen covered in powdered sugar and cocoa powder, with a pan of brownies half-devoured on the stove. Something was going on with our daughter.

Thankfully, Ellie was ready to be honest. She shared with me that she was struggling with the desire to end her life. Months later, she admitted that she had an eating disorder. I’m thankful that we found a wise, supportive therapist who directed us, step by step, in Ellie’s recovery journey. This therapist also knew when Ellie needed a higher level of care, which brought us to an eating disorders treatment center. Ellie spent the next seven months in various programs, such as partial hospitalization, residential, and intensive outpatient.

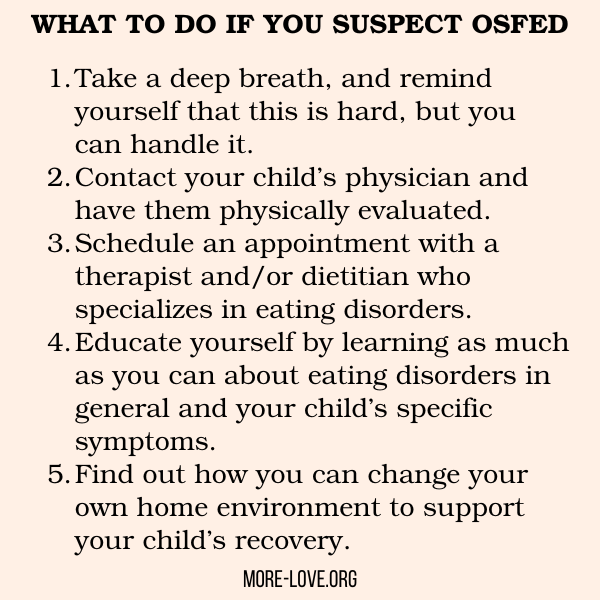

Getting a diagnosis

The treatment center diagnosed Ellie with “Other-Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder” (OSFED), which I had never heard of. But OSFED is actually the most common eating disorder diagnosis for adults as well as adolescents, affecting all genders. According to the National Eating Disorder Association, the OSFED diagnosis “was developed to encompass those individuals who did not meet strict diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or binge eating disorder but still had a significant eating disorder.”

It is just as severe and life-threatening as other eating disorders. In Ellie’s case, her eating disorder manifests in binging, purging and restricting, in various ways. But it’s a more invisible disorder. Her body size doesn’t reveal the chaos inside her soul.

Feeling like an outsider in eating disorder treatment

There were moments when Ellie felt like an outsider because of her OSFED diagnosis. When the treatment center celebrated teens who overcame their fear of gaining weight to taking a second helping of cake, Ellie felt dissonance, knowing that she struggled with the opposite problem.

When her nutritionist tried different methods to help her eat multiple portions of dessert, Ellie felt too shy to tell her that the binge voices in her head were getting louder, not quieter. When our insurance company threatened to stop approving residential treatment after ten days, because Ellie’s weight was stable (although her disorder was anything but stable), she felt betrayed.

Despite those moments of dissonance, the structure, support and tools of the treatment center were instrumental in helping Ellie recover. Because an eating disorder is an eating disorder.

Deception, hiding, and control

Eating disorders have similar characteristics, even when the behaviors look different. They specialize in deception, hiding and control. Eating disorders are often an attempt to conceal or manage deep pain. They result in self-hatred and shame.

It helped me to separate the eating disorder from my daughter. I realized that in Ellie’s darkest moments, the eating disorder was controlling her thoughts and behavior, which meant that she acted out in ways that shocked and disappointed me. I could have more compassion when I understood her illness better. I remembered how I had engaged in similar dark behaviors as a bulimic teenager.

We found our way forward by asking for and receiving as much support as we could find. For patients, the treatment center community offered classes, group therapy, exposure therapy, nutritional support, monitored meals together and social learning.

Getting parenting support

For parents, the center offered parent classes, which I attended as much as possible, plus weekly sessions with the therapist and nutritionist to learn how to support our daughter.

With the nutritionist’s coaching, I took on the role of supporting Ellie’s meals at home, through the Family-Based Treatment (FBT) model. That meant that I followed her nutritionist’s food plan to plate all meals, support Ellie in eating them (or offer liquid supplement when she refused) and supervised her post-meals to prevent purging.

Ellie both hated and needed this structure. She resented and resisted meals, so we battled it out. It took awhile for me to learn how to firmly stand up to my daughter’s eating disorder when she refused to eat. Parenting my daughter through an eating disorder became a part-time, if not full-time job, in addition to the one that I was paid for.

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Free Guide: How Parents Can Help A Child With An Eating Disorder

Master the secrets to supporting a child with an eating disorder. Thousands of families like yours are stronger today because of these six vital lessons drawn from lived experience, best practices, and extensive study.

Recovery was like a rollercoaster

Ellie’s recovery journey was like a rollercoaster. She progressed, then paused, then progressed, and then relapsed into even more self-destructive tendencies. As she healed, her eating disorder fought harder. She missed an entire semester of school because she was fighting for her life in a treatment center.

Often, it felt like our lives revolved around Ellie’s needs and appointments. My husband and I wrestled with how to support Ellie’s siblings, as we worried about neglecting them in the midst of attending to the crises frequently surrounding their sister.

After seven months in a treatment center, with almost constant parental supervision (prescribed by Ellie’s therapist) for at least three months, Ellie healed enough to discharge from treatment. In the past three years, we have made Ellie’s recovery a priority in terms of our time, our finances, and our activities. Ellie still meets with an eating disorder therapist twice a week and a nutritionist weekly.

Ongoing support

My husband, Ellie and I meet regularly with a family therapist (who specializes in eating disorders) who guides us in supporting Ellie, working through conflict, and bringing challenges to the surface before they blow up. This family therapist supported us when Ellie relapsed and guided us into appropriate next steps. She helped us learn more about how to support our daughter as we uncovered other conditions like ADHD.

While Ellie still has her challenges, she knows that my husband and I are in this with her. She knows that she has a strong support team to walk her through anything that comes up. And I’m grateful that the days of binging, restricting and purging are in the rearview mirror, as Ellie keeps choosing the recovery path, one day at a time.

Serena Menken writes books and articles that capture the unique moments of gut-wrenching pain and heartfelt joy experienced by parents of teens with mental health concerns. She counts each day of her three decades of recovery from bulimia as a gift. However, nurturing her oldest daughter through a similar disorder proved to be even more challenging and ultimately rewarding. When she’s not writing, Serena works full-time as a nonprofit leader, enjoys her three teenage children, and bikes through forest preserves with her husband. You can find Serena at her website and on Substack.