Many studies have found tremendous benefits in the Mediterranean Diet, but it may surprise you to know that it’s about so much more than food, and its social aspects can help with eating disorders.

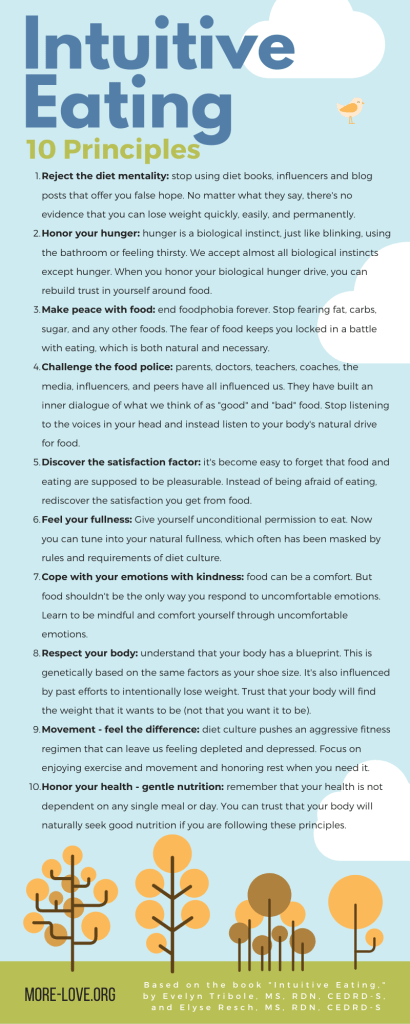

The word diet literally means the food we eat. But none of us eat food without cultural forces that shape how we feel about food, ourselves, and each other. And today the word diet typically means eating in a certain way to achieve weight loss. Most mainstream diets (e.g. Atkins, Noom, Intermittent Fasting, Weight Watchers, etc.) prescribe detailed food plans as the path to weight loss. They rarely address the social aspects of eating, and in fact their rigid programs often interfere with socializing.

Conversely, the Mediterranean Diet does not have rigid food rules and has not been strongly branded and capitalized on as a path to weight loss. While the Mediterranean Diet does suggest general types of food, the important detail is that in the Mediterranean region food is social and cultural. We can apply the social aspects of a Mediterranean style of eating to eating disorder recovery and feeding. This means the focus is not on the food, but rather on how food is prepared, shared, and eaten in community with others.

We aren’t supposed to eat alone!

Humans are highly social animals. We evolved to procure our diets, prepare food, and eat food together as a group. We were never meant to eat alone, but rather as a part of our social activity. Yet today, most of us shop for food, prepare food, and eat food alone. And we do this often while heavily distracted by non-human social proxies like social media or television.

Have you noticed how hard it is to eat food without the distraction of other people, even if they are virtual and through a screen? That’s a biological adaptation. We aren’t supposed to eat alone!

What is the Mediterranean Diet?

In its simplest form, the Mediterranean Diet is described as a diet rich in fruits and vegetables, grains, seafood, nuts, and fats. From a nutritional standpoint, the Mediterranean Diet prioritizes plants over animals, locally-sourced and in-season food, and foods that are close to their natural state vs. highly processed.

When seen this way, the Mediterranean Diet is not limited to a specific cuisine and can be applied within many other cultural food traditions. In other words, you don’t have to eat Mediterranean foods to benefit from the Mediterranean approach to food.

Beyond food, the Mediterranean Diet is also strongly associated with the following lifestyle factors:

- Shared meals: people are more likely to eat together and treat food as an important part of their day

- Family and food traditions: people are more likely to see food as a family activity that is an essential tradition and bonding opportunity

- Social activity: people gather together socially and have stronger social networks

- Life/work balance: people take a full lunch break, take Sundays off, and generally protect the balance between life and work

These key elements of the Mediterranean lifestyle are not common in American families, even if they are eating Mediterranean food.

Pro-health benefits of the Mediterranean lifestyle

The health benefits of following a Mediterranean lifestyle include:

- Lower risk of dementia by 23%

- Lower risk of early death

- Lower risk of cardiovascular diseases and overall mortality

However, focusing solely on the nutrients involved misses the potential opportunity for using the Mediterranean lifestyle on a broader scale. Simply adding walnut oil to your cooking is unlikely to bring the full benefits of the Mediterranean Diet, since the true value likely lies in the overall lifestyle, including social connections and food traditions.

We know, for example, that actual and perceived social isolation are associated with increased risk for early mortality. In fact, the quality of social relationships far outweighs other factors we frequently associate with a healthy lifestyle, like not smoking and physical activity.

There is evidence that the Mediterranean focus on the social aspects of eating is associated with better health for adolescents. This lines up with the research supporting family meals as a way to improve nutrition and mental health in children and teens:

- “The frequency of shared family meals is significantly related to nutritional health in children and adolescents. Children and adolescents who share family meals 3 or more times per week are more likely to … have healthier dietary and eating patterns than those who share fewer than 3 family meals together. In addition, they are less likely to engage in disordered eating.” Pediatrics

- “[R]egular family meals were a protective factor for mental health.” This includes mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders as well as fatigue, forgetfulness, irritability, concentration, and sleep difficulties. PLoS One

The Mediterranean lifestyle for treating eating disorders

The true value in the Mediterranean Diet is not just about what is eaten, but how we eat and how we feel when we eat, which is why it can help with eating disorders. Feeding a child with an eating disorder is not easy, but using the social elements of the Mediterranean lifestyle can help.

To apply the principles of the Mediterranean Diet in eating disorders treatment and recovery, consider the following steps:

- Daily family meals

- Socializing when eating

- Cooking and preparing food together*

- Sitting together at the same table to eat

- Sharing meals with family and friends

- Establishing a sense of community and well-being when eating

- Talking about the sensations of hunger, satiety, appetite and preferences without judgment or criticism

- Not using devices and distractions at the table*

*Unless prohibited/prescribed as part of FBT treatment for an eating disorder

The simplest strategy you can implement is focusing on family meals in eating disorder recovery. These should include the following elements:

- Everyone (or as many family members as possible) eat together

- Same time, same place, same food

- Parents focus on positive environment for everyone

Any meal works! If you can’t do dinner, can you do breakfast or a late snack? Adding family meals may seem like a major hurdle for your family, but it will likely make a big impact on your child’s mental and physical health. Is there some small step you can take today to help your family benefit from this aspect of the Mediterranean lifestyle?

Ginny Jones is the founder of More-Love.org, and a Parent Coach who helps parents who have kids with eating disorders.