Grace reached out to me with a common question, “I want to talk to my kids about food but it’s really scary with all the junk out there and my youngest doesn’t eat vegetables and my oldest is restricting; I don’t want to make things worse but I don’t know what to do.”

Grace has two kids, and she worries about different problems with each. With her youngest, she worries about binge eating foods like chips and cookies. With her oldest, she worries about restrictive eating, skipping meals, and weight loss. She’s afraid that either or both are developing an eating disorder. And her fear leaves her paralyzed. “I don’t know what to do or say,” she says. “It seems like no matter what I say, it’s wrong for one or both of them. So I’m trying not to say anything, but that’s no good, either.”

She’s not alone in this fear, so to work through some options and ideas, I interviewed Heidi Schauster, MS, RD, CEDS-S, SEP. Heidi is a nutrition therapist and Somatic Experiencing (SE) Practitioner in the Greater Boston area who has specialized in eating and body-image concerns for nearly 30 years. Her most recent book, Nurture: How to Raise Kids Who Love Food, Their Bodies, and Themselves, addresses many of parents’ biggest concerns about raising kids with a positive relationship with food and their bodies.

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Free Guide: How Parents Can Help A Child With An Eating Disorder

Master the secrets to supporting a child with an eating disorder. Thousands of families like yours are stronger today because of these six vital lessons drawn from lived experience, best practices, and extensive study.

Widespread food fear

One of the biggest challenges facing parents today is the tremendous quantity of moral judgment and fear around food. While this has been an issue for decades, the Internet and social media have amplified it. In the past, fearful food messages were limited to traditional media formats, which allowed for some gatekeeping of the message. It was imperfect at best, but there were limits on the quantity of information disseminated.

Today, anyone can start a social media brand, blog, or Substack and share their personal and unqualified beliefs about food with millions of people. One of the best ways to go viral on these platforms is to stoke fear and confusion, then provide the illusion of certainty with a simple program or product guaranteed to bring results. Springboarding off diet culture’s proven playbook, individuals with no formal nutrition training and questionable intentions have massive audiences with whom they share alarming food messages.

“There’s so much information out there about food and what you should eat and shouldn’t eat,” says Heidi. “We hear things like ‘This food is good and this food is bad.” There’s so much polarity. What I encourage parents to do is talk about food in a more pleasure-oriented way that centers connection. I encourage parents to make food with their kids and make mealtime pleasant because you want them to appreciate the other aspects of eating beyond nutrition.”

“In fact, I don’t think young kids need to learn much about nutrition,” says Heidi. “They have plenty of time to do that when they’re adults. More than anything, kids need to learn that food helps them get through their day and be able to focus at school. It helps them to be able to ride their bike and do all the things they like to do. And eating is a place and time where we rest, stop what we’re doing, and nourish ourselves and each other. I suggest we focus more on nourishment and less on nutrition.”

Kids learn about food by example

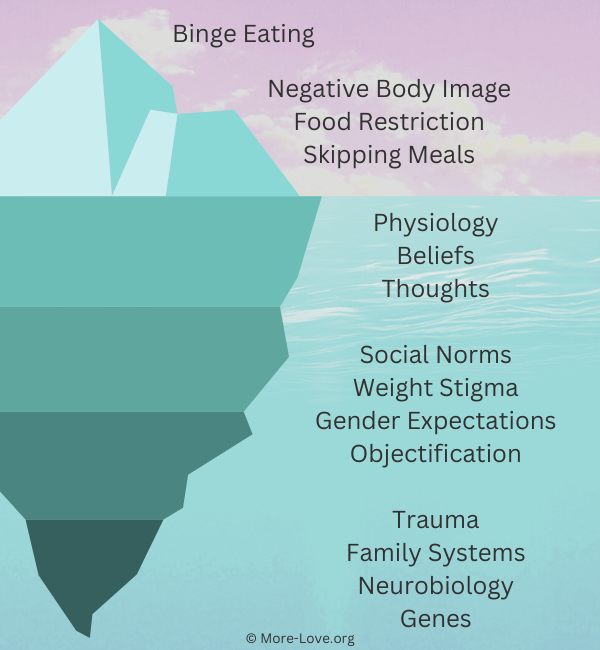

Diet trends go viral daily on social media, often suggesting we cut out certain nutrients or entire food groups. Parents do their best to be rational about restrictive diets. Nonetheless, children instinctually interpret food restriction as a symptom of fear. When food gets charged with fear, the risk of disordered eating, including binge eating, restriction, and purging, increases.

“There’s so much fear around what we eat on the Internet,” says Heidi. “And there’s nothing wrong with wanting to take good care of your body and feed it well and take care of it. But fear-based messages around food for whatever reason are not helpful.”

“It’s common for parents to follow a prescribed plan or eliminate certain foods or whole food groups,” says Heidi. “Then it’s tricky to figure out how to communicate that to their kids. For example, they know their kids need carbohydrates, but the parent doesn’t want to eat them. So how do they navigate that space?”

“And my answer is you have to eat them,” says Heidi. “You do this partly for yourself because our brains and bodies need carbohydrates. But also, your kids are watching you. If you want them to eat a diverse, well-balanced diet and have an open palate, then you have to show them by example. They absolutely pick up on whether or not Mom is eating the same things as everybody else.”

Relaxing your food fear

Of course, parents don’t have absolute control over how their kids feel about food, but we are very influential. Since we are bombarded with daily messages about food fear, it’s important to model a secure, unafraid relationship with food.

“I think being as relaxed as possible in our own relationship with food and our bodies is so helpful,” says Heidi. “As parents in this culture, we all must do our own work. We need to examine our biases around bodies and our attitudes about food so that we can be as relaxed as possible for our kids.”

“I think one of the reasons we get uptight about food is that our lives feel chaotic, and it feels good to have our ducks in a row about our food,” says Heidi. “But many times, it’s displaced control, and it’s not actually helpful. If the parent or the food environment is stressful or rigid and there’s a lot of anxiety around it, then children take that on.”

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Free Guide: How Parents Can Help A Child With An Eating Disorder

Master the secrets to supporting a child with an eating disorder. Thousands of families like yours are stronger today because of these six vital lessons drawn from lived experience, best practices, and extensive study.

Managing disordered eating patterns

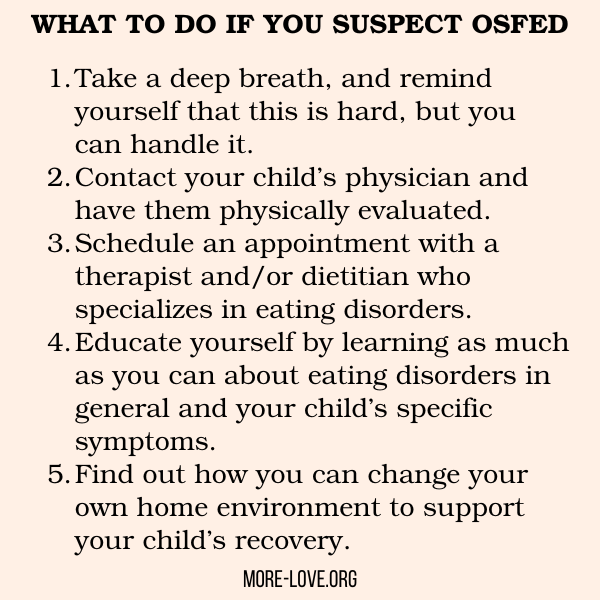

Parents can and should work on our own relationship with food. Meanwhile, if you’re seeing disordered eating behaviors in your child or teen, have them evaluated for an eating disorder. Beyond that, reading a book like Nurture can be very helpful. You can also work with a non-diet RD to create a meal structure and plan that works for your family.

“I love it when families are willing to examine what they might be able to do differently in their family culture around food,” says Heidi. “I know that family culture around food isn’t the only influence on disordered eating, but it is important in the healing process to do what we can at home to create a nourishing environment.”

“This is not about saying you’re to blame if your kid has trouble with food or that it’s all about you,” says Heidi. “There are so many factors that put someone at risk for an eating problem of any type. But I think parents have influence and need support if they have a child struggling.”

Ginny Jones is the founder of More-Love.org, and a Parent Coach who helps parents who have kids with eating disorders.