Emotional eating is a way to define a disordered way of eating, and it’s strongly associated with childhood trauma.

That’s what led Brittany to call me about her daughter Candice. “I’m worried that she’s emotional eating,” Brittany said. “Candice has always been anxious, and she’s experienced some serious social and medical trauma. She’s always loved sweets, but lately, it’s as if she’s addicted to cake and candy. She just can’t get enough. It’s causing her a lot of pain, and she cries because she’s so miserable. I want to help her, but I don’t know how.”

I understand. Watching your child go through this can be excruciating. Brittany has been doing the best she can by trying to limit sweets, but it’s backfiring. “The less access she has to sweets, the worse it gets,” she says. “I keep finding evidence that she’s eating them every day even though she swears to me she doesn’t want to. She keeps begging me to help, but I don’t know what to do.”

Free Download: How To Parent A Child With An Eating Disorder

The 6 basic steps you need to follow to help your child recover from an eating disorder.

I know how badly Brittany wants to help Candice feel better, so I walked her through how childhood trauma can impact emotional eating and how common approaches like limiting sweets can make the problem worse, not better. Brittany changed her approach and is now on the path of supporting her daughter with childhood trauma and disordered emotional eating.

Does childhood trauma cause emotional eating?

Yes, childhood trauma is a major cause of disordered emotional eating. Disordered eating behaviors span a range of severity, from disordered emotional eating to binge eating disorder. Disordered eating is strongly associated with trauma. According to a recent study, over 80% of Americans diagnosed with binge eating disorder experienced childhood abuse, neglect, and other forms of trauma.

Many people can imagine using food as a psychological coping behavior. It’s commonly suggested that food and eating are a disordered way to soothe unhappy thoughts and feelings.

This suggests that disordered emotional eating is a mental process that can be changed with new/better education. It perpetuates the false belief that eating disorders are a choice and that someone can simply “choose” to recover from them. However, disordered eating is rarely an educable condition. In fact, most people who have disordered eating are exceptionally well educated about what they “should” and “shouldn’t” do with food.

Effective treatment must address the biological, psychological, and social causes of eating disorders.

Food is naturally soothing for many complex biological reasons. Therefore, all eating is inherently emotionally-driven. Disordered emotional eating is rarely a simple mental issue of seeking comfort through food.

Emotional eating, binge eating, and food addiction cause a great deal of distress and are not mental choices. It’s not as simple as saying “I feel stressed, so I’ll eat,” and lacking the self-control to do otherwise. Rather, several physiological cues including hormones and brain pathways drive obsessive thoughts about food and a compulsion to eat beyond comfort.

How does trauma impact emotional eating?

Trauma has a physiological impact on the body that can lead to adverse health consequences including disordered eating. These consequences are not due to active mental choices. They are responses to internal signals and drives outside the person’s rational, decision-making brain.

Keep in mind that almost all the brain’s activity is non-conscious. Scientists estimate anywhere from 80-95% of how our brain functions is non-conscious. Therefore, most of our behaviors are “driven” more than “chosen.”

For example, researchers have identified a particular brain circuit that is susceptible to the impact of trauma and chronic stress, leading to its dysfunction. Additionally, certain hormones, including acyl-ghrelin, often called the “hunger hormone,” are associated with emotional eating and binge eating. These processes are completely outside of conscious awareness or choice and can’t be overcome with food rules and willpower.

Body Image Printable Worksheets

Colorful, fun, meaningful worksheets to improve body image!

- Boost confidence

- Improve self-esteem

- Increase media literacy

How do I know if my child has disordered emotional eating?

Ultimately all eating is emotional. It’s encoded in our DNA to find food emotionally stimulating and pleasurable.

There’s a difference between everyday emotional eating and disordered emotional eating. It’s important not to pathologize kids’ natural hunger and appetite. For example, there’s nothing wrong with enjoying sugary treats, salty snacks, and other highly palatable food. It’s genetically programmed.

Likewise, it’s completely normal for people to occasionally eat more than is technically necessary to meet their caloric needs, even to the point of physical discomfort.

On the other hand, if your child appears to be obsessed with food or feels a compulsive need to eat beyond comfort repeatedly, they may be struggling with disordered emotional eating. Obsession is defined as having constant thoughts, cravings, and fantasies about food. Compulsion means feeling as if you are out of control and there’s a disconnect between conscious choice and behavior. The key difference between intuitive eating and disordered eating is not so much what’s happening with food but how it feels. Someone with disordered eating experiences extremely high levels of distress related to food and eating.

If you’re concerned that your child has disordered emotional eating, please reach out to a trained non-diet professional. It’s vitally important that you seek someone who operates from a non-diet or anti-diet perspective to avoid adding more shame to your child’s relationship with food.

What types of childhood experiences create trauma associated with emotional eating?

Childhood experiences of trauma are highly correlated with disordered emotional eating, including:

- Emotional neglect, emotional abuse, physical neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse

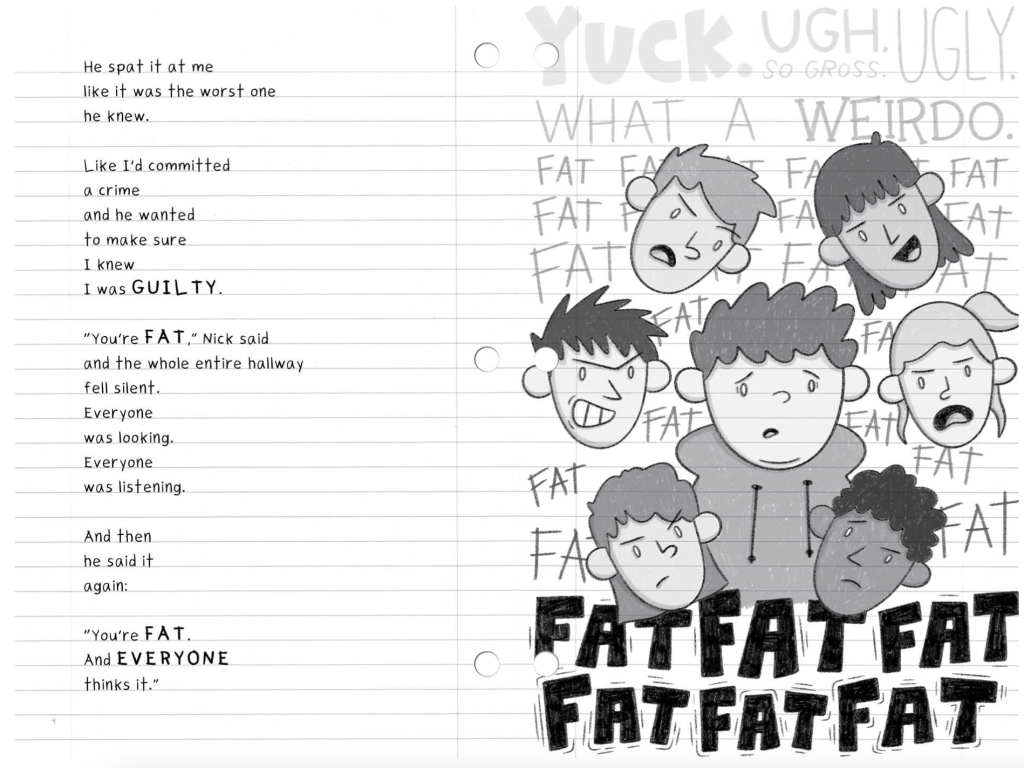

- Victimization and shaming, including teasing, criticism, bullying, and social exclusion

- High levels of emotional dysregulation

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Elevated adverse childhood experience scores (ACEs)

- High levels of childhood cumulative trauma and emotional abuse

The link between childhood trauma and disordered emotional eating has been largely overlooked in both scientific literature and common culture due to outdated beliefs that eating is 100% within mental control. The belief that willpower and food rules can overcome disordered eating is outdated and counterproductive.

People with disordered emotional eating are accused of poor judgment, intellectual capacity, and morality. They are given nutrition information, told to “just eat less,” and “just stop eating.” This approach increases trauma around food, eating, and self-worth. In other words, common approaches to disordered emotional eating increase trauma and make things worse.

Free Download: How To Parent A Child With An Eating Disorder

The 6 basic steps you need to follow to help your child recover from an eating disorder.

Rather than assuming that people who have disordered emotional eating are lazy, weak, or immoral, we should support them in getting treated for childhood emotional neglect, abuse, and trauma. As long as we continue to treat emotional eating as a moral failure, we impose further trauma upon someone who is already traumatized.

What are the symptoms of emotional eating caused by childhood trauma?

Most disordered emotional eating behaviors are driven by non-conscious processes including brain activity, hormones, and hunger cues. We must be careful not to be too focused on the thoughts and beliefs that surround disordered emotional eating since these are often an over-simplification of a complex behavioral pattern.

Observable behaviors of emotional eating

- Eating large quantities of food

- Feeling full but continuing to eat anyway

- Eating to the point of physical discomfort

- Intentionally restricting food for long periods

- Forgetting or avoiding eating for long periods

Thoughts and beliefs about emotional eating

- I’m always hungry

- I can’t stop myself

- It’s as if I’m controlled by food

- I use food as a way to cope when I have big feelings

- It feels as if I’m addicted to food

- I forget to eat and get too hungry

- When I feel stressed or excited, I eat

- I want to stop, but I can’t

- I hate myself for eating this way

- Make sure I don’t do it by never buying that food

- Keep me away from that food

Many times parents, loved ones, and well-meaning healthcare providers assume thoughts and beliefs are the cause of emotional eating. However, this can lead to inadequate and even harmful treatment approaches.

For example, when providers assume thoughts are the cause of emotional eating, they may suggest treatment that limits access to food and minimizes eating pleasure. Paradoxically, this approach often increases hunger, which cues the drive to binge eat. In other words, it backfires and causes more harm than good.

It also perpetuates the experience of trauma by treating the person as if they are bad or make bad choices.

What are the different types of emotional eating?

There is a continuum of eating behavior that ranges from intuitive eating to various forms of emotional eating. The symptoms differ in terms of severity, level of obsession, degree of compulsiveness, and how much a person is distressed by their behavior. Here is one way of identifying different patterns of eating:

1. Intuitive eating

This is when a person eats according to hunger and appetite approximately every 2-5 hours throughout the day. They typically don’t feel either extreme hunger or extreme fullness and have a peaceful relationship with food.

2. Mindless eating

This is when a person eats without paying attention to hunger cues but purely in response to emotional or environmental cues. For example, they may eat in response to feeling stressed or bored. Or they may eat because the food is in front of them, such as when there’s a candy jar on the counter.

3. Restrictive + binge eating

This is when a person restricts food in an attempt to control their behavior, only to become overwhelmingly hungry and have a binge eating episode to make up for missed calories. While this may look like emotional eating, oftentimes it is a response to physiological hunger cues, though they are often below the level of consciousness.

4. Binge eating episodes

These are when a person is not restricted and feels adequately fed but eats a large quantity of food in a short period. Research has shown that this is often in response to a physiological, non-conscious drive to eat rather than a mental choice.

5. Binge eating disorder

This is when a person has repeated binge eating episodes. Many times these people are in a restrict + binge eating cycle. Increasingly, binge eating disorder is seen as a physiological response to restriction combined with differences in brain functioning and hormones. Binge eating disorder is strongly associated with a history of weight-based teasing and criticism from family, peers, and healthcare providers, repeated experiences of weight stigma, restrictive eating patterns, and weight cycling caused by dieting.

Free Cheat Sheet: Body Positive Parenting Essentials

⭐ Support your child in developing a healthy body image

⭐ Learn the essential steps and family rules you need to have in place for positive body image.

⭐ Make your home more supportive for everyone with six simple steps that anyone can do.

How to help your child who is using emotional eating to cope with childhood trauma

Your child can recover from both childhood trauma and emotional eating, and parents are key to the process. You can help your child heal from their trauma and support them in moving towards recovery from emotional eating. Here are five things to keep in mind when parenting a child who has childhood trauma and disordered emotional eating:

1. Inventory past experiences

Seek to understand how traumatic experiences have impacted your child. In addition to classic forms of trauma, look for very common but often overlooked forms of emotional trauma. For example, have they been teased, bullied, and criticized by peers, coaches, teachers, healthcare providers, siblings or parents? This is especially common if they are/were in a larger body.

2. Process your feelings

Get support if you feel guilt or shame about your child’s experiences. Parents are all doing the best we can, but sometimes our children still experience trauma in childhood. Before we can support them fully in recovery, we need to heal ourselves. Get professional support and guidance so you can process your feelings about your child’s trauma.

3. Seek trauma treatment for your child

Cognitive behavioral therapy is the most common therapy in the United States, but it’s not often the best approach to healing childhood trauma. Seek options like EMDR, somatic therapy, trauma-informed therapy, and psychodynamic therapy, which are generally better at uncovering and addressing childhood trauma.

4. Create a positive eating environment

Rather than try to change or fix your child’s eating behavior right now, begin by improving their eating environment. Trauma is healed in loving, accepting relationships. How you approach eating with your child can either help or hinder their care, so get some guidance about increasing and improving your child’s eating experiences with you. The less you try to “fix” your child’s eating by controlling their access to food, the greater your chance of leading them toward healing their relationship with food. If you need support with what to feed your child, find a non-diet dietitian who can help.

5. Ditch the myths

Stop repeating popular myths about emotional eating. Most people see emotional eating as an issue of how someone thinks and what they do with food. They repeat popular myths like “just tell yourself to stop eating,” or “just stay away from sweets,” or provide nutritional facts and information. These approaches are popular and make a lot of intuitive sense, yet they are harmful and dangerous. Most people who have disordered eating are already more aware of common food rules and nutritional advice than the average person. Eating myths cause harm by increasing a sense of shame and judgment for people who have childhood trauma and emotional eating. Simple, easy fixes that have been repeated ad nauseam for decades don’t address childhood trauma and emotional eating. And they can cause more harm than good. Please seek support and guidance to optimize your ability to support your child.

Ginny Jones is the founder of More-Love.org, and a Parent Coach who helps parents who have kids with disordered eating and eating disorders. Combining science, compassion, and experience coaching hundreds of families, she helps parents understand what’s going on with their kids’ eating behaviors and teaches them the science-backed skills to heal kids’ relationship with food, improve their body image, and feel better about themselves, their relationships, and life in general.

Ginny has been researching and writing about eating disorders since 2016. She incorporates the principles of neurobiology and attachment parenting with a non-diet, Health At Every Size® approach to health and recovery.